Secundino Zuazo was born in Bilbao in 1887 and is mainly known for his work in Madrid in the pre Civil War period. Zuzao was an older member of the group of young architects called the Generation of 25, named after the influence that the Decorative Arts Exhibition in Paris in 1925 had on them. Contemporary with the G.A.T.E.P.A.C group in Barcelona, the members of Generation of 25 were interested in promoting a new rationalist architecture to replace the regionalism that was prominent in Spain at the time. Zauzo was regarded as one of the leading architects in Spain for his design of the Recoleto Pelota court, an early concrete shell structure that he designed with Eduardo Torroja in 1935, the Nuevos Ministeros, 1933-35, and especially, the Casa de las Flores apartments that he designed with Torroja in 1930-1931.

After attending the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, in 1925, Zuazo traveled in the Netherlands where he came in contact with the work of the Amsterdam School, its planning principles and use of brick. Zuazo was also known for his design of the Madrid Urban Planning Project of 1930, a project done with the German planner Hermann Jansen. This was for part of the expansion of rectangular blocks proposed in the Castro Plan of 1860, for the ensanche area to the north of the central city. This plan was contemporary with Ildefons Cerdá’s plan for the expansion of Barcelona in 1859, that proposed a similar system of blocks for the ensanche. About this time, Zuazo was commissioned by a real estate company to design an apartment building for rent on a complete block in the Argüelles district of Madrid. The idea was to design a prototype manzana that could then be duplicated in this undeveloped area. It was to be a model for building in a new hygienic city with good light, ventilation, with terraces and gardens.

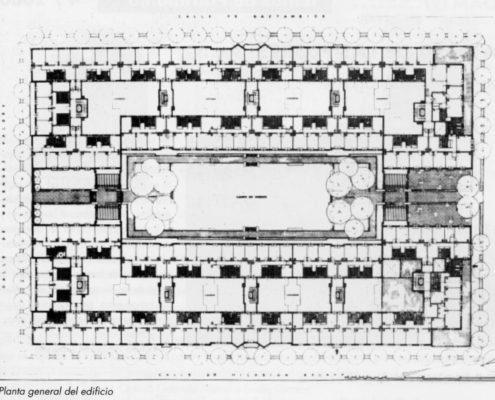

The blocks in the Madrid ensanche are 120 x 80m in size, aligned north and south. They were typically developed as perimeter blocks with infill buildings aligned along the streets forming shared courts on the interior of the block that grew in ad hoc fashion over time. Zuaca, however, proposed making the block with two long “C”-shaped double slabs that align on the long sides and enclose a large garden on the interior of the block. Gates and small courts make entrances at the ends. Each “C” element consists of two parallel slabs that enclose a long interior patio and wrap the ends forming additional patios at the ends. The slabs on each side are organized with service spaces along the patios and living areas and bedrooms facing either the street or the interior garden. The patios function as service courts and stair towers alternate with one-story laundries to divide the patio into smaller courts. The stairs thus serve apartments on each side of the double slab. This arrangement has several advantages. First, the living spaces in each apartment overlook landscaped areas, either the street that is lined with mature trees or the landscaped garden on the interior of the block. Separating what is essentially a double-loaded slab into two zones of dwellings with a 9meter open space between allows for windows on both sides of the individual apartments and improved cross ventilation and natural lighting for entrance halls, baths, and kitchens. The 9-meter width of the slab also means that natural light from the patio can be admitted into the interior hallways by putting windows in the doors.

The perimeter slab organization may have similarities with Dutch and German precedents, however, the variation of building heights, treatment of the corners, and entrance details are quite different. The perimeter surfaces along the streets are 6 floors height with a narrow, 4-story zone mid-block that marks the main entrance to the garden. On the long sides of the garden, the slab is 8 floors high with an open, timber-framed pergola and tile roof at the top. This way, more apartments take advantage of the garden that, even with the increased height, is a very open, well-lighted space. At the south end, the buildings steps back at the outside corners. Cantilevered balconies equipped with flowerpots wrap the corners creating the effect of a vertical flower garden and hence the name House of the Flowers. Other details enhance the corner treatment, French doors on the rooms opening to the balconies, an arcade supporting the terrace above the ground floor, and retractable awnings are used to shade the balconies. The idea of making the block with narrow slabs instead of the usual accumulative perimeter infill was a feature of the Cerda Plan but is also something Zuaco would have seen in his experience in Holland.

The building contains 288 flats that appear in 21 variations of the basic type organized into 10 departments each with 4, three or four bedroom flats organized around a stair and elevator stack. Each department has entrances along the street and garden. Along the street there are 17 shops that alternate with the department entrances. The basic structure consists of parallel bearing walls spaced 4.5 meters apart and iron floor joists on 60 cm spacing. Catalan vaults are used in the stairs and the top floor of the central 8-story slabs is timber framed and covered with a tile roof. The street and courtyard walls are brick that are slightly decorated at the ground floor in a manner reminiscent of Amsterdam school details. The patio walls are plaster. Only a few window sizes and types are used and these are equipped with various combinations of shutters, roll-up blinds, awnings and window balustrade, and balconies. While the varied massing of the “manzana”, the use of brick, arches, the decorative detailing around entrances, and the pergola on the roof of the central slabs seem to define an architectural language different from other rational buildings of the period, the large garden, the use of narrow slabs, very repetitive plans, and the functionalist quality of the stairs, windows and balconies are certainly “rationalist” features. The difference between the density of Casa de las Flores and that of the surrounding blocks in the Argüelles district is striking, 57% coverage as compared to 85% of the typical block, but size and quality of the interior gardens is a benefit that outweighs the loss of higher density.

Casa de las Flores suffered serious damage during the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939 when the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda lived here for a time and the building was shelled.recently, it was designated a historiclandmark as an example of early modernist architecture in Spain, and in 2003 work was begun to completely restore and modernize it. In light of the current emphasis on green architecture, the name implies a more extensive example of green building; the flowerpots only occur on a few terraces. Still, the dominant image of the corner balconies on the south, the serene landscape of the interior garden and the application of environmental features like the windows, lighting, and ventilation define Casa de las Flores as an important early example of green building and suggest a new way to design a garden city.

Information provided in part by: http://housingprototypes.org