'People die and they are not happy' – architecture can't change that. A place of rest, a space for silence: that is something it still manages to provide, despite the fact that not even stones are as heavy as they were in more solid epochs with a firmer belief in the eternal, as in Saqqara, as in Giza, for example.

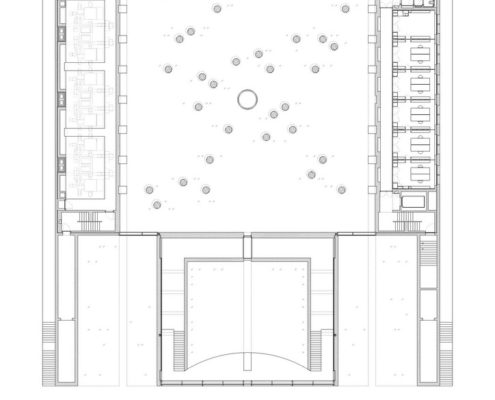

Our final road is uncertain. Neither church nor temple of the dead offer a model for the path to nothingness or angelhood. In lending shape to freedom and necessity, the intensity, the texture of a Maghreb mosque comes closest to meeting the task: a Piazza Coperta, a place in the middle of this cenotaph, where many can assemble and yet the individual is shielded; a catalyst for all our feelings. In this room – 5000 years young – the columns with their capitals of light establish the only reference left to us: a cosmological contrast between populated stacks of clay and the sun with its light.

The ceremonial halls – two for 50, one for 250 people – are simply boxes of split stone, set open-fronted into a second, slat-steered casing of glass: the departed soul, the coffin, the urn has gone before already, into the realm of light, is at one now with the heavens, the clouds, the trees.

Like no other building – the Museum in Bonn and the Chancellery in Berlin are no exceptions – this one reflects the unbroken will of the architects. A hollowed, jointless block 50 by 70 meters, 10 meters deep in the earth, 10 meters high above it, one stone, one grave-stone, insisting on the material consistency of its several spaces. And if there were a word of truth in Ludwig Wittgenstein's claim that architecture 'compels and glorifies; that where there is nothing to glorify there can be no architecture', then this structure glorifies the quintessence of architecture, celebrates space, the silence of walls in light.

Information provided in part by: ArchDaily