Development of Museumsinsel (Museum Island), previously known as the Spreeinsel (Spree Island), began in the sixteenth century as a pleasure garden for the Stadtschloss (City Palace). The Altes Museum (Old Museum) by Karl Friedrich Schinkel was completed in 1828, and then in 1841 King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia ordered his court architect, Friedrich August Stüler, to draw up a plan to develop the land behind the Altes Museum – hitherto used for commercial purposes – and create a ‘sanctuary for the arts and sciences’. Designed by Stüler, the Neues Museum (New Museum) became the first component of this visionary haven, and was erected between 1841 and 1859. The Neues Museum was the first three-storey museum ever built and was organised as a solitaire construction executed according to a simple ground plan that enclosed two courtyards and replaced the central rotunda and cupola used in the Altes Museum with a rectangular stair hall that rose through all floors and occupied the full width of the building.

Extensive bombing during World War II left the building in ruins with some sections severely damaged and others completely destroyed. Few attempts at repair were made after the war, and the wreck was left exposed with only a minimum of consolidation and protection undertaken during the GDR period. After David Chipperfield Architects’ appointment to the project in 1997–98, the building and restoration took nearly eleven years to complete, and the entire Museum Island was added to the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage list in 1999.

The project was unique given that no earlier reconstruction attempt had been fully realised over a relatively long period of quiescence. Its patron's original intention of linking museum design and presentation in a symbiotic relationship of exhibits and exhibition spaces had not only lost its appeal for the contemporary visitor but in many cases could simply no longer be created since much of the original material – both artefacts and rooms – no longer existed, especially in the larger spaces where this didactic unity was originally most apparent.

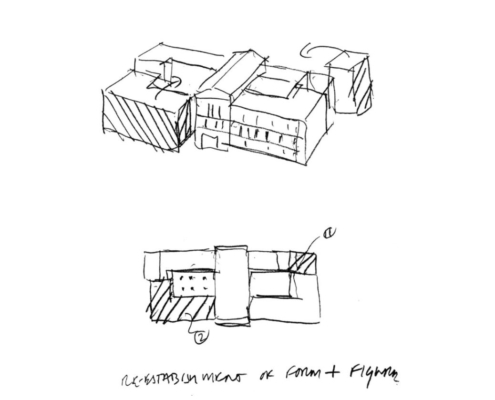

When considering the way forward, it was clear that the ruin should not be interpreted as a backdrop for a completely new architecture but neither was an exact reconstruction of what had been irreversibly lost in the war seen as an option. A single continuous structure that incorporates nearly all of the available damaged fabric while allowing a series of contemporary elements to be added became the preferred path, often described as ‘the third way’. The key aims of the project were to recomplete the original volume, and to repair and restore the parts that remained after the destruction of World War II. The process can be described as a multidisciplinary interaction between repairing, conserving, restoring and recreating all of its components. The original sequence of rooms was restored with newly built sections that create continuity with the existing structure. The almost archaeological restoration followed the guidelines of the Charter of Venice, respecting the historical structure in its different states of preservation. All the gaps in the existing structure were filled in without competing with its brightness or surface. The restoration and repair of the existing elements of the building were driven by the idea that the spatial context and materiality of the original structure should be emphasised – the contemporary reflects the lost but without imitating it.

The new exhibition rooms are built of large-format prefabricated concrete elements consisting of white cement mixed with Saxonian marble chips. Formed from the same concrete elements, the new main staircase repeats the formal idea of the original without replicating it, and sits within the majestic hall that is preserved only as a brick volume, devoid of its former ornamentation. Other new volumes – the north-west wing, with the Egyptian court and the Apollo risalit; the apse in the Greek courtyard; and the South Dome – are built of recycled handmade bricks, complementing the preserved sections. With the reinstatement and completion of the mostly preserved colonnade at the eastern and southern sides of the Neues Museum, the pre-war urban situation is re-established to the east. A new building, the James Simon Gallery, will be constructed between the Neues Museum and the Kupfergraben, echoing the urban situation of the site pre-1938 when Schinkel’s Packhof (Customs House) faced the Spree.

In October 2009, after more than sixty years as a ruin, the Neues Museum reopened to the public as the third restored building on Museum Island, exhibiting the collections of the Egyptian Museum and the Museum of Pre- and Early History. The building bears witness to its complex history while some of its original technological innovations have been laid bare. The very incompleteness of its decorative pattern helps to create a holistic understanding of the historic and contemporary structure and its original and current purpose.

Information provided in part by: David Chipperfield